As part of the UQ Union’s “Feminist Week”, the Women’s Collective brought a unique perspective of the legal industry through their “Women in Law Faculty Event”, held on Monday the 4th of April.

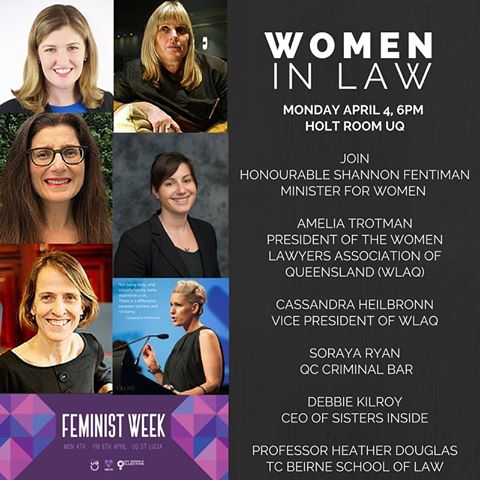

Five phenomenal women spoke about their experiences in the legal industry, the barriers faced by women in the profession, and ways for future young solicitors, barristers and legal professionals to overcome the same disparity.

Speakers included:

• The Honorable Shannon Fentiman (Minister for Women),

• Amelia Trotman (President of the Women Lawyers Association of Queensland; Accredited Family Law Specialist, Armstrong Legal),

• Cassandra Heilbronn (Senior Associate, MinterEllison and Vice President of Women Lawyers Association of Queensland),

• Soraya Ryan (QC criminal bar) and

• Debbie Kilroy (CEO of Sisters Inside).

The panel was moderated by Professor Heather Douglas of the TC Beirne School of Law.

Opening Remarks from Professor Sarah Derrington, Dean of UQ’s T.C. Beirne, School of Law

Whilst the feminist movement has been one of struggle and determination for women past and present, it is also imperative commence with a note of optimism. Pride should be the governing sentiment when reflecting on the success of women in the legal arena: we have a female Dean, a plethora of esteemed alumnae from UQ’s law school, including the likes of Dame Quentin Bryce AD, CVO, Catherine Tanna, and Catherine Holmes SC, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Queensland. There are astonishing women everywhere around us: the panellists, professional women, female teaching staff, and the overwhelming number of female students succeeding in law.

However, these achievements do not nullify the barriers faced by women in the legal industry. The case is not closed: barriers can be observed in the gender disparities of upper echelons of law firms and other legal positions, as well as gendered norms within workplaces that breed discrimination and sexual harassment.

Change is necessary within the industry. We are the agents of “creating change”, but first it is important to reflect on the current situation for women in the legal profession.

Heather: This engenders the question: what gender biases can be observed in the industry and what circumstances of discrimination have you faced?

Soraya: When I was at university, it never occurred to me that gender-based discrimination might have an impact on my career. But once I entered the ‘real world’ I became aware of instances of sexual harassment in my workplaces, sexism and gender-based discrimination. For the most part, sexist comments about me or gender-based discrimination affecting me was occurring behind my back. And I was not aware of it until after the event.

Amelia: Without always being outrageously blatant, micro aggressions also underpin the industry. Whilst some circumstances may seem trivial and harmless in character, when you reflect on the situation and consider that similar situations would never happen to a man working in the exact same position, it becomes apparent that the legal industry still reflects archaic gender norms. For example, when I was working as a solicitor in a small firm, one of the partners repeatedly asked me to make them cups of coffee. This seems “harmless” as it doesn’t reflect the same severity as workplace sexual harassment or offensive slurs, however it is still not appropriate – I was a solicitor, not a personal assistant.

In circumstances like these, it may be difficult to address the situation head on, but when I raised the issue, asking whether he would have asked a male solicitor to make him a coffee, he realized how his requests were governed by gender norms. He had never considered how his request would be inappropriate.

Another example of this is at the usual Friday afternoon drinks at this particular firm, where the male lawyers did not interact with the all-female support staff. Such a direct divide was confronting to me. Gender equality and representation in the industry is something that still needs significant reform in order to achieve substantive equality.

Shannon: Everyday occurrences of sexism are everywhere in the profession. In my time at the construction and manufacturing union (which is skewed significantly towards being a male-dominated industry), I was once referred to as the pet name “girly”, which definitely falls outside of what is appropriate and in essence is demeaning. Luckily, several other females and I called him out on it to address the slur, however, these instances should not be occurring in the first place.

Sexism insidiously weaves its way into our workplaces: politics is also laced with gender-based remarks. I frequently get asked about my hair, makeup, and age (whilst male politicians do not to the same extent), and once was referred to as a “wailing banshee”. In times like these, it is important to support other women to call out members of the profession who outrageously undermine the achievements and merits of women.

We must be active, not passive, leaders in our profession to mentor and support other women. When I was a Judge’s Associate, Justice Roslyn Atkinson was an inspiring role model: when I explained that I wanted to be an advocate, she proclaimed, “why don’t you want to be on the High Court?”. Women have the potential to achieve anything they set their minds to, and this serves as a reminder to aim high and to support other women within the industry.

Cassandra: Sometimes older women in the professional forget the importance of a supportive network. They faced so much discrimination, and this may result in resentment towards younger women in the industry and being less sympathetic towards the modern cause of professional feminism. However, this only holds women back: we need to be encouraging other women to break down gender norms.

Debbie: Law is teeming with able-bodied white men, especially in my specialty, which is criminal law. The result of this is twofold: men are representative far greater in the profession and, secondly, the law has developed to favour this demographic. In response to the first issue, I now have my own firm with an abundance of female lawyers. This has created a more co-operative and supportive dynamic.

In response to the latter effect, we see vast discrimination that is perpetuated by the law. For instance, women of colour, especially Aboriginal women in remote communities, do not have the same access to justice and protection by the law. A clear example of this is in frequent circumstances where these women may not have the language/comprehension skills to navigate complex legal questions, which are designed to essentially trip them up. If they are asked if they killed their husband, they might say yes, but there is a lack of further questioning to determine the circumstances behind the event. There may be a vivid history of domestic violence, which resulted in the need for self-defense, or any number of extenuating circumstances leading up the violent act. The law often ignores gendered narratives, and thus, has a detrimental effect on women, particularly Aboriginal women.

Heather: Gender biases lead to barriers. What do you think the barriers hindering women in the legal industry are?

Debbie: As there are few women practicing criminal law, this creates a cycle of disadvantage for aspiring female criminal lawyers. When the hiring team is completely male, it makes it difficult for women to get a foot in the door as they are more likely to hire other men. This is perpetuated by the stereotype that women are not robust or loud enough for the field. This stereotype is absolutely not representative of the truth – this is why it is essential to support other women.

Amelia: Another huge barrier relates to pregnancy and maternity leave. Employers vastly differ in their approaches to flexible working hours and their expectations of their employees. Top tier firms are often more willing to offer flexibility as opposed to smaller firms. Similarly, most small – medium size firms have no paid parental leave policy, leaving professional women in a very difficult financial position should they choose to have children. You also get this resistance to the paid parental leave argument from older women who did not receive the same assistance. This remains a great barrier for female legal professionals today.

Shannon: Another barrier is the disparity between female lawyers and those in senior positions. Approximately 61% of law school graduates are female, but the numbers in the upper positions offered by firms is appalling. There is a slow shift towards parity: we have seen some improvement over the last few decades, but this is not enough. These are more male CEO’s named Peter in the top 200 companies than there are women.

However, quotas are only a temporary solution: what we need is cultural shift that recognizes the value of women in competitive industries such as law. We need to encourage men to take time to care for children. We need more women in higher positions. Structural change will slowly lead to cultural changes.

Soraya: In criminal practice, often, clients will express a preference for a male barrister on the assumption that he will be ‘tougher’ than a woman barrister. Clients who have a choice about who they brief (usually not legally aided clients) may base their choice on appearances. Speaking generally, drug dealers and gang members may choose barristers based on image – who looks tough, who looks masculine, who looks most successful. Almost always they choose men. That choice does not necessarily mean that they win their cases of course, but until the focus is on merit, the focus on what is perceived to be ‘the right appearance’ will always be a challenge in criminal matters. In civil matters, my perception is that clients and solicitors choose the best person for the job – man or woman – because outcomes and not appearances matter.

Heather: Are there any other barriers and modern changes?

Cassandra: Generation Y is lucky in the sense that our male counterparts are not as likely to hold archaic biases. Most of us have grown up in households where both parents work, in comparison with generations before us. Hopefully this will lead to a cultural shift. Men also play an important role in changing the industry to one that reflects gender equality.

Amelia: Another barrier is the issue of self-worth. In my experience, I never see men struggling with gaining the confidence to ask for promotions if they believe that they deserve one. We need to be teaching younger women how to negotiate with male senior partners (where there is a huge power imbalance). Promoting self-worth is a tool that should be taught from a young age: without this encouragement, the cycle of an imbalance of men in senior positions will continue.

Heather: What piece of advice would you give to your younger self, as a law student or as a woman entering the profession?

Debbie: At its core, my advice would be to live your life each day, enjoy what you’re doing, and breathe it in. Build a strong network of women around you – they will support you, provide you with an invaluable wealth of knowledge and opportunities, and encourage you to achieve.

Soraya: If you work hard, and if you have skill, your merit will show through. There has been research done which suggests some gender-bias in outcomes in appellate matters in the High Court. I have heard a Justice of the Court of Appeal say, many years ago now, that women have to work harder than men to achieve the same outcome. I like to think that you can address potential bias by ensuring your written submissions are well crafted, so that you can impress the relevant judicial officer before you walk into the court room.

You could anguish all day about gender bias in the industry but that brings little or no benefit. My advice is to build and treasure your networks and support one another and strive for excellence in all that you do.

Amelia: I would advise myself to find a mentor and develop a network. This allows one to develop a sense of deeply set self-worth, guide you, and may even get you a job too!

Cassandra: I’d tell myself to stop looking for 100%. You can’t physically do everything! I’d be lying if I said it was possible to be perfect in every arena of your life. It’s important to find a balance between studying hard, working, maintaining relationships, and ensuring positive mental health. It’s okay to not be perfect at everything all the time – you don’t want to burn out either.

Shannon: Dream big!

Debbie: You have the power to help the most disadvantaged groups in the community. Don’t forget both compassion and passion – you can do amazing things and make a difference to society.